News

Record breaking Henley Masters Regatta returns for 31st Year

No such thing as Henley blues as the Masters Regatta roars back into life

“The day we got our kit we were running around the hotel, screaming with excitement”

GB senior squad athletes Lizzie Witt and Miles Beeson share their memories of racing at GB v France

Across The Line: Records tumble on finals day of Henley Royal Regatta

Our Henley Royal Regatta finals day debrief, and what happened over 10 hours of racing at Talkin Tarn Regatta

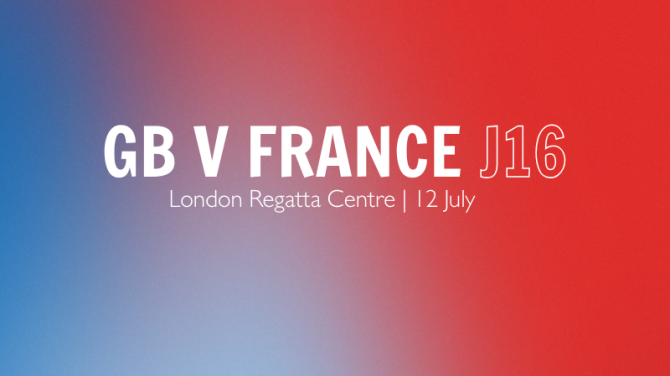

London Regatta Centre to host Annual GB v France Competition

Fifty-four J16 athletes and eighteen coaches and support staff, many of whom are volunteers, have been selected to represent Great Britain at the 43rd GB v France match

British Rowing Member Prize Draw – July 2025

We have one Henley Women’s Regatta Teddy Bear to give away in this month’s exclusive British Rowing member prize draw

Read MoreA right Bobby Dazzler! Newcastle University back in the final of the Island Challenge Cup

After the race of the day, Newcastle University are back-to-back finalists at Henley Royal Regatta

Read MoreThames RC ‘A’ vs De Hoop: A HRR rivalry with three wins in three years for the Tideway club

Three years, three races, one result – we dig into this enduring, international battle between the booms

Read MoreLondon RC braced for redemption rematch in the Thames Challenge Cup

London RC reach the final of the Thames Challenge Cup for the first time since 2006

Read MoreThe story behind Bristol University Boat Club’s record entry to Henley Royal Regatta

We caught up with Senior Coach Freddie Bryce in the boat tents at HRR to talk about Qualifiers, their week of racing so far and what’s next for this exciting club

Read MoreRosa Millard and Thames RC set for a title defence at the British Rowing Club Championships

After winning the Mixed Eight amongst other events, Thames RC are back for more, and there are some brilliant prizes on the line

Read MoreHistory made as the Bridge Challenge Plate takes flight

Marlow RC write itself into the history books as the Bridge Challenge Plate makes its debut at Henley Royal Regatta

Read More“It has really bonded us”: Mother and son race at Henley Royal Regatta

Lizzy of London RC and Felix of Tideway Scullers both qualified their boats for HRR and had the incredible experience of competing in consecutive races down the iconic course

Read MoreBritish Rowing expand indoor rowing partnerships with Dixons Academies Trust

British Rowing and Dixons Academies Trust deliver a new indoor rowing partnership, breaking down barriers to participation

Read More‘We’ve got 42 students qualified’: Dominant depth on day two of Henley Royal Regatta

Molesey BC and the University of London shine as records are broken on the second day of Henley Royal Regatta

Read More